COVER STORY

Bangladesh has always lived close to nature. The rhythm of its rivers, the pulse of its monsoon, and the warmth of its sun have shaped not only its landscape but its way of life. For centuries, homes and courtyards were designed in quiet harmony with the climate: shaded verandas that caught the breeze, open courtyards that held light, and deep eaves that softened the rain.

As cities have grown taller and faster, that rhythm has begun to fade. The conversation between people and their environment—between comfort and balance—has slowly been replaced by glass walls and mechanical air. Today, that dialogue is returning. Across Bangladesh, architects are rethinking how buildings can once again respond to their surroundings. They see sustainability not as a trend or a checklist but as a way of belonging, a return to the wisdom that once defined our built environment.

Among them, Ar. Enamul Karim Nirjhar, Ar. Nazli Hussain, and Ar. Bayejid Mahbub Khondker bring three distinct perspectives to that shared idea. Their works—a poetic residence, a living green headquarters, and a humane industrial landscape – reflect a growing movement that seeks to reconnect architecture with climate, culture, and community.

The Storyteller of Space — Ar. Enamul Karim Nirjhar In the quiet of another corner of Dhaka stands a house that feels like a dream you can walk through. Walls rise and fall like verses; light drips through perforated ceilings, and a tree pierces straight through the living room. This is the Chaabi House, created by Ar. Enamul Karim Nirjhar, founder of System Architects and a living testament to his belief that “form follows fiction.’’

Nirjhar is a polymath. He is an architect, filmmaker, lyricist, and cultural provocateur. For him, design is not just about solving problems; it’s about telling stories.

“Architecture is not only about structures,” he says. “It’s about stories, the lives, dreams, and memories that inhabit space.”

In the Chaabi House, sustainability is not treated as a checklist but as a living character within the story. The house opens itself to air, filters sunlight through layers of greenery, and rests on a foundation of local materials such as brick, terracotta, and reclaimed wood.

It breathes naturally, staying cool without dependence on machines, and every wall and opening feels intentional, crafted not just for function, but for feeling. The result is a home that doesn’t just respond to the climate; it converses with it. You can smell the rain here before it falls. You can hear the silence between wind and wall.

For Enamul Karim Nirjhar, sustainability is cultural continuity. He sees it as the act of preserving emotion, memory, and craftsmanship in a world that often replaces depth with efficiency. His architecture sustains the intangible, the feeling of belonging, the sense of place, and the poetry of life itself.

In a career spanning decade, Nirjhar has become one of Bangladesh’s most influential creative voices reminding us that architecture must not only save the planet but also save our sense of wonder.

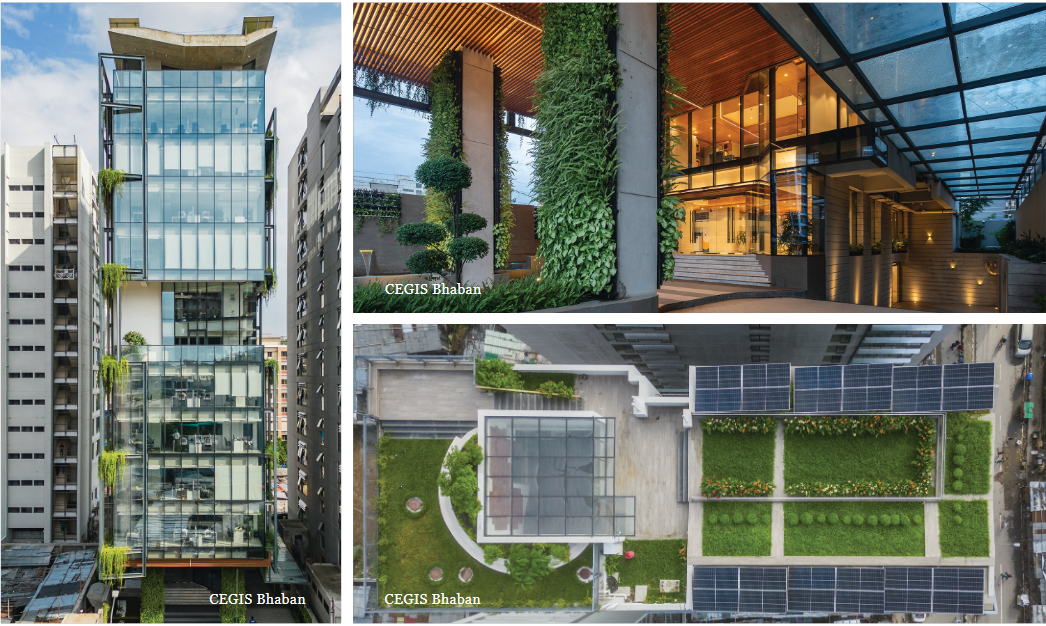

The Architect of Balance — Ar. Nazli Hussain In the dense heart of Dhaka, a building rises softly behind a curtain of green. It’s glass façade shimmers through leaves, the air feels lighter, and the atmosphere hums with quiet balance. This is the CEGIS Bhaban, the corporate headquarters of the Center for Environmental and Geographic Information Services, designed by Ar. Nazli Hussain, founder of Praxis Architects.

Nazli is a LEED Accredited Professional (BD+C) and USGBC Faculty Member, recognized as the first Bangladeshi architect to earn this international green certification from the U.S. Green Building Council — a global standard known as LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), which measures how environmentally responsible and energy-efficient a building truly is. Her approach to architecture merges science with empathy.

“Architecture is the balance between people, nature and the built environment, while prioritizing the performance of our buildings to secure a greener future,” she says.

That philosophy shaped every corner of the CEGIS Bhaban, which serves a government trust dedicated to sustainability, water management, and climate resilience. Nazli’s vision was to create a building that not only performed efficiently but also “felt alive” — a place where design, data, and well-being could coexist.

Inspired by the Japanese concept of Shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing, she imagined the structure as a vertical forest within the city. The façade’s Vertical Greenery System (VGS) acts like living skin, cooling sunlight before it meets glass and filtering the air naturally. Drip irrigation nourishes the plants with harvested rainwater, while solar panels atop the green roof generate renewable energy. Inside, open workspaces glow with daylight, reducing the need for artificial lighting. CO₂ sensors ensure clean air, while views of greenery from every desk maintain a sense of calm and focus. The building breathes, saves energy, and nurtures the people who inhabit it, a rare achievement in Dhaka’s urban density.

Completed in 2024, the CEGIS Bhaban stands as a quiet revolution — proof that technology and tenderness can shape a truly sustainable architecture. In Nazli’s work, performance and peace coexist. Her design doesn’t just promise a greener future; it already lives it. The Humanist of Brick — Ar. Bayejid Mahbub Khondker

Far from the capital’s bustle, in Rangpur, another kind of building hums with life. Here, the air smells of clay and sun-dried earth. Women sit weaving rugs under dappled sunlight.

Laughter, work, and wind move freely through the space. This is the Karupannya Rangpur Factory, designed by Ar. Bayejid Mahbub Khondker, principal of Nakshabid Architects. A project that redefines what an industrial building can be.

Bayejid didn’t design a factory that consumes; he designed one that gives back — to the workers, to the landscape, and to the sky. The long brick walls breathe with air. Courtyards punctuate the plan, creating lungs that flush out heat and flood the interiors with light. The structure itself is made from locally sourced brick, grounding it in its region and reducing the carbon footprint of transport.

The Karupannya Factory isn’t only sustainable in its materials, it’s socially sustainable. Hundreds of women artisans work here in dignity, surrounded by light and openness, their craft intertwined with nature. By day, sunlight warms the textured walls; by night, the bricks hold the day’s heat, releasing it gently. The architecture follows the rhythm of the people inside, not the other way around.

“True sustainability is circular by design, demanding not just a low carbon footprint, but a handprint that is positive — leaving the community, the ecosystem, and the future richer than we found it,” says Architect Bayejid.

Bayejid’s work bridges vernacular wisdom and modern efficiency. He believes that the lessons of traditional rural homes — courtyards, shaded verandas and natural airflow can guide even the most contemporary of structures. His sustainability isn’t just technical, it’s rooted in respect: for the worker, for the craft, for the land. In his hands, a factory becomes a field; an act of making becomes an act of healing.

The Green Thread That Connects Them

Three architects. Three visions. Three different ways to define sustainability.

Nazli Hussain measures it with sensors, sunlight angles, and precise calculations.

Bayejid Mahbub Khondker, humanizes it in the warmth of brick and the dignity of work.

Enamul Karim Nirjhar, narrates it turning sustainability into an emotion that lingers long after the story ends.

Their buildings stand in different cities, serve different functions, and speak different languages, yet they are all rooted in the same truth.This is Bangladesh’s new green renaissance, born not from imported ideas, but from its own soil, craft, and conscience. These architects are not just designing structures, they are designing mindsets.

And as a new generation of designers, landscape architects, and thinkers follow in their footsteps, one thing becomes clear: the future of Bangladesh will not only be built—it will be grown. Because in the end, architecture is not about how tall a building stands, but about how softly it touches the earth.